The Shore Interview #55: Kevin Clark

Questions by Ella Flores, Interview Editor

EF: It’s a pleasure getting the opportunity to interview you, Kevin. To start off, I’d like to pose an intentionally broad question based on your wide literary citizenship. Between your third full 2022 poetry collection, The Consecrations, and your 1984 and 1990 chapbooks, and of course critical essays throughout, could you speak to how you personally see the concept of literary citizenship having evolved over that period of that time?

KC: I taught for almost two decades at the Rainier Writing Workshop, and one day after one of my reviews had just come out, I was startled when a colleague told me that I was a “good literary citizen.” I was happy to hear such a thing, but I’d never considered the idea per se. Outside of family and friends, my adult life has always been an immersion in literature. For me, this meant writing poetry and criticism, reading poetry voluminously, talking books books books, teaching poetry writing and literature, giving and attending readings and talks, and, later, having the honor of being poet laureate of San Luis Obispo County (CA). I love the ongoing relations I have with so many of my former students. This life remains fun, like a calling or a personal mythos by and in which to live.

When I heard the term “good literary citizen,” it seemed tinged with a kind of responsibility, a charge to do something that you may not always choose to do. But that’s rarely ever been my experience. Since I was a kid, I’ve been enraptured by the way words revealed and enlarged the world. Literature—especially poetry—offers me a way to create an aperture into a small province of what’s heretofore inaccessible. Writing, reading and talking about literature is my good fortune. Literary citizenship for me has been living this privileged life.

EF: And if you’d entertain an additional question, what aspects you’re surprised to be more relevant than ever from your 2007 poetry writing textbook, or what you’d want to add or change in it today?

KC: I wrote The Mind’s Eye: A Guide to Writing Literature (from Pearson Longman) a couple of decades ago and, to my mind, poetic aesthetics haven’t changed that much. The text is still in print. The poems I read in The Shore are not substantially different in aesthetic stance from those I may have seen back then in Ploughshares or The Western Humanities Review.

If I had to cite a section that seems more relevant than ever, I’d have to choose the chapter titled “The Poetry of Witness,” in which I take up political poems. I was always a political person, but I was writing The Mind’s Eye before the MeToo movement and Black Lives Matter and transgender rights and the very real rise of repressive autocratic forces in our country and around the world.

Nevertheless, the textbook holds what I believe are extraordinary poems about racism, sexism, homophobia and other socio-political challenges. In fact, your question sent me back to the book—and I was surprised to see how many political poems are spread throughout, not only in “The Poetry of Witness” chapter. As we know, poets have forever been called to consider injustice as a subject and I’m happy to remember that the book offers so many models of good political poems. I’d be remiss if I didn’t add two things: first, no poet should feel pressured into writing about any subject, and second, too many political poems I read today are preachy or excessively didactic or lacking in imagination. As I say in The Mind’s Eye, some poets are so filled with rage about an issue that they sacrifice the aesthetic quality of the poem—and thus they may reduce complexity and communicate less effectively.

As to what I may wish to add, while I believe my pedagogical comments all pertain well today, I think I’d include more model poems about the way authoritarian legions restrict our freedoms. In fact, I might include a poem from the current issue of The Shore, Julia C Alter’s poem “Migration Season in Vermont,” which is remarkable in its seamless connections.

I’d also add a section about the way the so-called new sciences can, as a poetic subject, enhance consciousness. Finally, I’d include new comments about online journals and submissions.

EF: I’m in love with the final sentence of “Rue,” quoted here: “How the comic / Bronx plosives of long-gone men in love / with a game and each other return to flood me / despite the would-be shield of my art.” There’s a wonderful interplay between musicality and rhythm that creates so much tension and release in this closing. What are some both trusted and novel veins of musical inspiration you find yourself tapping into to channel this musicality into your work? And has the role it plays in your poetic processing and exploration changed for you much over time?

KC: Well, first off, thanks for your generous comment—and for publishing “Rue.”

I must say, for many years now I’ve enjoyed blending somewhat disparate dictions in a poem. As for inspiration, I’m a big fan of poets such as Lynda Hull and Thylias Moss, that is, those who find ways to include both quotidian dialect and formal expression in a single poem. In the case of “Rue,” I found myself melding slightly elevated diction with that of a more old-time northeast vernacular common to my parents and relatives. I was born in New York City and raised in New Jersey. Though I’ve lived in California for decades, my wife will tell you that my Jersey lingo can return without warning.

When I was writing my second book, Self-Portrait with Expletives, I gained enough confidence to begin mining the old family way of speaking. It’s not something I always turn to in my work, but it’s a melodic option. That way of speaking forms a kind of kindred music in my ear. Exploiting such expression is more intuitive than anything else. In the thousands of micro decisions that go into any one poem, sound is my first determiner. In Jersey talk, there exists a clipped rhythm and an intimating style of stresses, both of which combine to convey myriad shades of emotion. Not long ago, in the journal Raritan, I published a short story, titled “Jersey Sand,” and the narrator tries to describe the ethos behind the speech:

“All the stereotypes—the humped shoulders, the low plosives out of the puckered lips, the jaw pushed forward like a boat’s prow, the feigned surprise with the bulging blood-shot eyes, the voice raised at the bare hint of offense, the rat-a-tat-tat of one syllable words—are you kidding me? It’s honest performance. Says you’ve got the kind of know-how comes from a life stripped of bullshit.”

As seen in innumerable movies and TV shows, I think the inhabitants themselves can get a kick out of their own accent, especially when it’s heightened by faux mockery or one-upmanship or simple raised emotion. Thus, the “plosives” can seem “comic.”

Among other things, I think “Rue” is about the tension between the overwhelming threnodic heartwaves I can feel when thinking of my father and uncle (both of whom died in their forties) and the need to avoid the kind of excess sentimentality that can turn a poem into blubber. I didn’t realize it when I was writing the poem, but now I think the more formal elements of expression (“the taut craft of loss”) render the need to constrain what may seem like childish emotion, while the more vernacular language (“The Globe giving him / the five-finger salute behind a waggish puss / while snatching the one-spot”) mimics the language the three profoundly beloved men would have used themselves, thus making me feel their absence that much more intensely.

As for the last lines you ask about, I’d like to think they are uttered in what I call a falling ghost pentameter. I hope the earlier rhythms of the poem set up the final decrescendo of sound and emotion. Again, such a diminuendo happens due to myriad sensations at the moment of creation, not a mechanistic or conscious series of decisions.

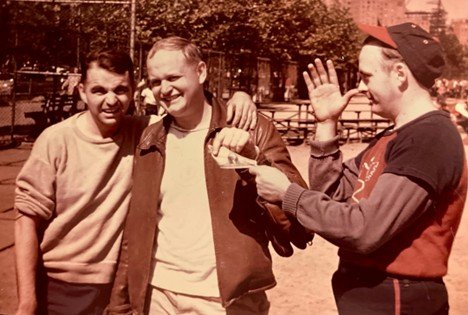

Finally, here’s the photo upon which the poem is based:

Kevin Clark Rue Photo

EF: Throughout “Fuselage” (and to a lesser degree in “Rue”), there’s a lovely invocation of poetry and/or reference to the poem itself, within the poem. Whether seen as a meta reference, writing about writing, or something else entirely, how and when do you see the inclusion of the poem within the poem as a potent craft choice?

KC: Poems thrive on surprise. Whatever the poet can do to make the reader sit up and take notice can be helpful, right? In theatre and cinema, I’ve always enjoyed the breaking of the fourth wall. I’ve also enjoyed voice-over. (I’m thinking especially of, say, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and Blade Runner). Breaking from the established narrative can provide an effective strangeness.

In “Fuselage,” the speaker’s fear of flying leads to questions about death—and then to anxieties brought on by certain aspects of postmodern thinking. I know I was reacting against the notion that there’s no such a thing as an author, that the only thing that exists is material, that all beliefs are easily deconstructed. I didn’t realize it as I was writing, but I think such quick associative movements may offer a similar, “potent” strangeness.

The associative jump from a common nervousness about flying to a more disturbing disquiet about the foundational nature of human existence sets up the “poem within the poem.” Matthew Arnold may have called these different loci “actions.” On one hand, the speaker wants to enjoy the altitudinous beauty. He looks forward to seeing his family at home. On the other hand, he’s confronting challenges about the reality of beauty and family. The poem pings back and forth between the two actions. I hope that readers may themselves find a kind of disquieting effect in the alternating, quite oppositional points of view.

EF: Are there any journals or magazines you're currently enjoying?

KC: Funny, but on considering your question, I was surprised to realize how many different journals I can find myself reading at times. Let me note four: When I was in my twenties, The Georgia Review was both very inexpensive and bulging with great literature. I’ve been subscribing since. Though a bit different in taste, over time its four editors—Stan Lindberg, T.R. Hummer, Stephen Corey and Gerald Maa—have maintained exceptionally high standards, so much so that the overall impact never dissipates. I can say the same for The Southern Review, which I’ve read for at least the last twenty-five years or so. Jessica Faust publishes a wide range of poetry that is often remarkably akin to my own preferences. I also enjoy The Threepenny Review, which has some of the most idiosyncratically interesting writing anywhere. Wendy Lesser curates everything from topnotch poetry to photographs to the brilliant miscellany of the Table Talk section. Finally, let me put a good word in for Radar Poetry, which like The Shore, is an online journal of exceptional verse. Rachel Marie Patterson and Dara-Lyn Shrager have a sharp editorial eye for the kind of taut, urgent poetry that responds to the public and private severities of our time.

EF: Please speak to how two poems in this issue of The Shore (not including your own) are in conversation with each other.

KC: I was moved and impressed by so many of the poems in the current issue. Indeed, it seems to me that many of the poems talk to each other. Several are individually in conversation with an intimate second person “you,” who is in some way distant or absent. Some find inventive and persuasive ways to engage political issues. Rilke is probably my favorite poet and it seems the issue is invested with a Rilkean impulse to examine a lost or incomplete self not only in relation to others but in relation to one’s own imagined identity. I found alluring linkages in four poems: Emily Rosko’s “Limerence Ode,” Sarah Horner’s “Asclepias,” Christopher Buckley’s “Profligate” and Sumayya Arshed’s “I’m Sorry I Forgot You after the Funeral.”

These last two seem to own a gorgeous threnodic yearning. In Buckley’s deeply affecting, imagistically fluid “Profligate,” the speaker appears to be elegizing himself, as if his life—and perhaps all human life—is vaporous. It seems he’s disappearing before himself. The poem questions the usual primacy people grant themselves. What does the history of a lived life add up to? Buckley answers that “the past is a fine powder / on the road that ends at the sea…”

Moving insightfully back and forth between the settings of the deathbed and the grave on one hand and her own ardent musing on the other, Sumayya Arshed’s “I’m Sorry I Forgot You after the Funeral” is likewise concerned with the insubstantiality of human existence. The intimate “you,” probably an elder, has died and, as much as the speaker wishes to keep hold of the deceased, she can’t: “in the exam room of memory, / i bundle your voice into a fist, and it slips / through my finger.”

I find myself responding to the oceanic sense of loss in both poems.

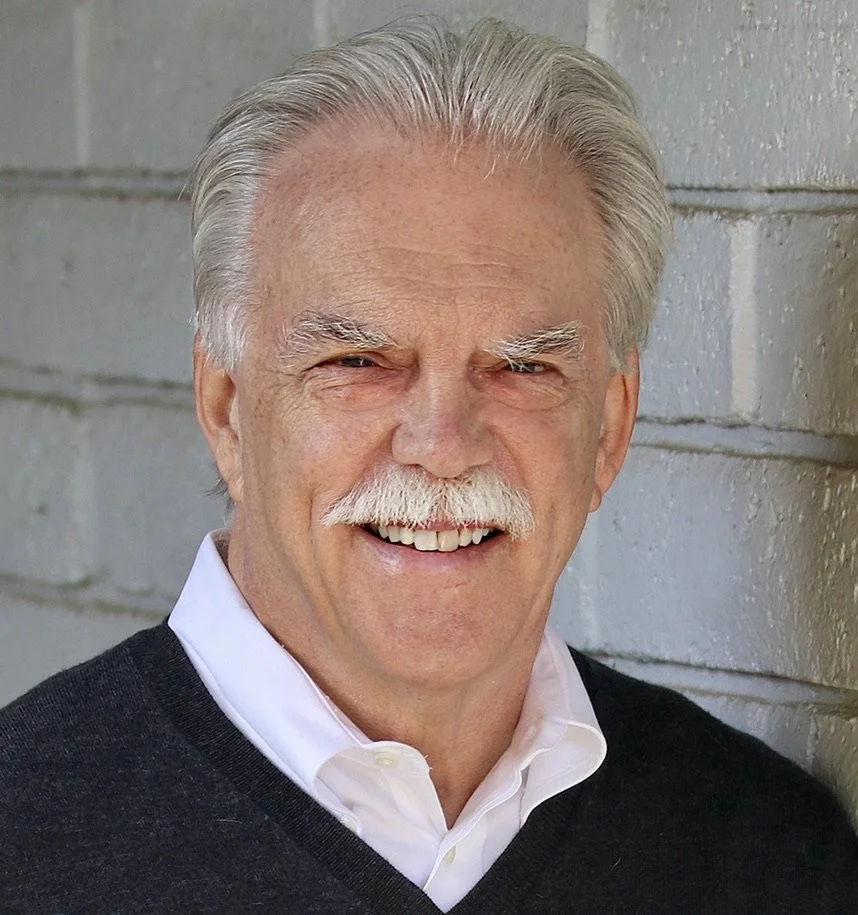

Kevin Clark